In the history of toys, few creations stand out as a more audacious and emotionally charged departure from the norm than the "Little Miss No Name" doll. Produced by Hasbro for a single, fleeting year in 1965, this 15-inch doll was not designed to be a companion for tea parties or a fashion model. Instead, she was conceived as a figure of profound pathos. A symbol of vulnerability crafted to elicit a sense of empathy and compassion from the children who might adopt her. Her brief existence on store shelves belies her enduring legacy as a sought-after collectible and a powerful, if unconventional, statement in the world of play.

The doll’s very conception was a direct response to the dominant toy trend of the 1960s, a trend almost single-handedly defined by Mattel's global phenomenon, Barbie. While Barbie embodied glamour, aspiration, and a world of endless fashion and accessories, Hasbro’s design team, led by artist Deet D'Andrade, chose to go in the exact opposite direction. They decided to create a doll that had nothing. This strategic choice was not merely a marketing gimmick; it was a psychological experiment in toy design. Designers crafted Little Miss No Name as a doll without comforts, leaving her barefoot with a messy mop of dirty blonde hair. They clothed her only in a tattered burlap sack, held together by a single safety pin, to emphasize her impoverished state.

The aesthetic of Little Miss No Name was heavily inspired by the "big-eyed waif" paintings of American artist Margaret Keane. Keane's work, which depicted forlorn-looking children with disproportionately large, expressive eyes, was a cultural touchstone of the era. By translating this artistic melancholy into a three-dimensional toy, Hasbro aimed to create a character that would tug at the heartstrings of both children and their parents. The doll's most striking features were her enormous, sad brown eyes. Also the single, perpetual plastic tear that clung to her cheek—an unshakeable symbol of her sorrow. Her arms were even designed to extend in a posture that resembled a plea for comfort or charity. This was a deliberate design choice intended to deepen the doll's narrative of destitution.

Hasbro’s marketing campaign for Little Miss No Name was as unique and emotionally manipulative as the doll itself. The television commercials and packaging art were a stark contrast to the vibrant, sunny advertisements for other toys. The doll was portrayed in a cold, dim alley, with snowflakes drifting down. Emphasizing her plight as a child with no home and no one to care for her. The jingle was a mournful ballad, and the tagline was a list of her non-possessions:

“She doesn't have a pretty dress. She doesn't have any shoes. She doesn't even have a home. All she has is love.”

The box itself contained a poignant message that read,

“I need someone to love me. I want to learn to play. Please take me home with you and brush my tear away.”

This powerful plea for adoption was designed to tap into a child's natural nurturing instincts, fostering a sense of empathy for those less fortunate.

However, the doll’s unconventional design proved to be a double-edged sword. While it successfully captivated some, it reportedly repelled many more. Rather than evoking the intended compassion, the doll’s sad, forlorn look unsettled or even frightened many children. Its melancholic aesthetic struggled to compete in a market dominated by cheerful, aspirational characters.

It asked children to engage with a level of emotional depth that few toys had ever attempted. It seems the risk did not pay off. The doll was a commercial disappointment, and after a single year, Hasbro discontinued production. Its brief time in the spotlight led it to be largely forgotten by the general public. It was relegated to the "Museum of Failure" as a product that failed to understand its audience.

Despite its commercial flop, Little Miss No Name has achieved a remarkable second act. The doll's limited production run and unique, unsettling aesthetic have transformed it into a highly sought-after collector's item. Collectors of vintage toys are fascinated by its unusual place in toy history. The doll has garnered a passionate cult following. Its value on the secondary market can vary widely based on condition. A played-with doll might sell for $50 to $100, but a well-preserved example with its original burlap dress and accessories can command prices well into the hundreds. The most prized finds are those in mint condition, still in their original box, which can fetch upward of $500. A testament to how a commercial failure can become a rare and valuable treasure over time.

The legacy of Little Miss No Name is a complex one. She stands as a poignant reminder that toys can be more than just objects of entertainment; they can be vehicles for social commentary and emotional exploration. While she may have been a "scary doll" to some, to a dedicated community of collectors and enthusiasts, she is a unique and iconic piece of pop culture history. Her story is not one of commercial success, but of a bold creative vision that, despite its failure, created a truly unforgettable and emotionally resonant toy.

The 1960s was a fascinating time for toys, and "Little Miss No Name" wasn't the only doll designed to evoke a sense of empathy or sadness. A notable example is Susie Sad Eyes, a doll that shared a similar "big-eyed" aesthetic and melancholic expression. Created by American artist and toy designer June T. Fraser for Uneeda Doll Co., she was also a direct nod to the artwork of Margaret Keane.

Susie Sad Eyes was introduced in the late 1960s, a few years after Little Miss No Name. While she also had oversized, tearful eyes and a downturned mouth, she was a slightly less stark departure from the typical doll. She often came with more conventional clothing and accessories. Bridging the gap between a sad waif and a collectible fashion doll. Like Little Miss No Name, her unique design has made her a highly sought-after item among collectors today.

The toy industry's history is often defined by a battle between convention and rebellion, and today, that struggle continues in a new form. Mattel’s iconic Barbie, with her glamorous lifestyle and unrealistic body proportions, established a long-standing dominance in the doll market. Critics argue that this monopoly on beauty and aspiration limited consumer choice and perpetuated narrow beauty standards. But in recent years, a powerful counter-movement has emerged from independent creators and small businesses: the rise of the artisan doll.

These handcrafted creations offer a unique, personalized, and often socially conscious alternative. They move away from mass-produced uniformity and instead celebrate diversity in all its forms, from different body types and cultures to varied abilities. Unlike their commercial counterparts, artisan dolls are not just "pretty"; they are often designed to represent real heroes and reflect the rich tapestry of the human experience. This shift represents a broader cultural demand for toys that don't just entertain but also educate and inspire. By investing in these one-of-a-kind dolls, consumers are not only supporting small artists but also helping to shape a more inclusive and body-positive future, where play can be a vehicle for empathy, creativity, and genuine self-expression.

Libraries across the worldwide are transforming themselves by lending a variety of items beyond books and movies. This movement, known as the "Library of Things," allows patrons to borrow everything from practical tools to musical instruments, making expensive or rarely-used items accessible to everyone. This shift from content consumption to experiential learning is changing the very definition of a library.

In the United States, a number of libraries have launched innovative lending programs that feature American Girl dolls.

These programs go beyond simple playthings by using the dolls and their accompanying books as tools to teach history, encourage reading, and engage children in a hands-on learning experience.

The "Library of Things" concept is growing internationally, with unique and innovative lending programs emerging in various countries.

Some of the most popular items in these "Libraries of Things" are often the most unexpected. Here are a few examples:

This shift in library services demonstrates a commitment to serving communities in new and innovative ways. These programs not only save people money but also promote a more sustainable way of living by encouraging sharing and reducing consumption. We must Save Our Libraries!

At the intersection of art, activism, and history, Kudzanai Chiurai’s "The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember" is far more than a simple art installation. It is a profound, ongoing, and living archive that challenges the very nature of history and memory, particularly from a pan-African perspective.

A Living Archive of Pan-African History 📚

Chiurai has intentionally and meticulously assembled a collection of cultural ephemera. For example, the collection contains vinyl records, posters, and pamphlets. These objects directly oppose the sanitized narratives found in official archives. By focusing on these marginalized "things," Chiurai creates a space where the voices and stories of liberation struggles are not just remembered, but actively re-engaged with.

The project is a direct response to a fundamental problem of post-colonial societies. The archives of the past are often remnants of colonial power. They documented the history of colonizers, not the lived experiences or cultural richness of the colonized. Consequently, a vast amount of knowledge was lost or destroyed. Chiurai's library serves as an act of archival resistance. He reclaims and rebuilds a memory of the past from the bottom up, using objects that formal institutions deemed insignificant.

To fully appreciate the project, we must understand the artist. His name is Kudzanai Chiurai. He was born in Harare, Zimbabwe. The year was 1981. Chiurai belongs to the "Born Free" generation. This is a term for people born after Zimbabwe gained independence from British rule. This context is critical. It helps us understand his work. His art grapples with the unfulfilled promises of a post-liberation Africa. It also explores the complex legacy of colonialism.

His art is a powerful blend of media. He uses painting, photography, and film. He also creates installations. His work tackles urgent social issues. These issues include xenophobia and displacement. They also include cycles of violence and power. The Zimbabwean government once threatened him with arrest. He faced this threat because of his critical work. This led to a period of self-imposed exile. He lived in South Africa. This experience strengthened his resolve. He decided to use art as a form of activism.

His practice is a constant interrogation of power. He asks pointed questions. For example: Who writes history? Whose stories are preserved? Which ones are forgotten? "The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember" is his answer. It is a creative and rebellious act of memorialization. It highlights the voices and cultural artifacts of a people. These voices were often silenced.

What makes this project unique is its rejection of a traditional archive. Chiurai designed his library to be both iterative and collaborative. Every time the installation exhibits, a new "librarian" curates the collection. This process invites new perspectives and brings forgotten dialogues back into the light. This constant re-evaluation ensures the project remains a dynamic conversation, not a fixed monument to the past.

The project’s exhibition at the A4 Arts Foundation powerfully demonstrated this concept. For this specific show, a curator brought the project’s sound archive to the forefront. The curator took on the meticulous work of digitizing 30 vinyl records. This process captured not only the music and speeches but also the audible "patina of use"—the pops, crackles, and hisses that tell a story of their own. This act was not just about preservation. It honored the history embedded in each groove. By doing so, they preserved a crucial layer of aural history that would otherwise be lost.

Visitors to the exhibition could interact with reproductions of the vinyl covers printed on perspex. By placing these "records" on a specially designed listening box, they could hear the digitized audio. This innovative approach transformed a static archive into a visceral, haptic experience, bridging the gap between the physical and the digital. It allowed people to physically engage with the reproductions, mimicking the act of handling and playing a vinyl record, while the digital format made the invaluable content accessible to a broader audience who might not have had the opportunity to experience the original objects.

"The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember" is part of a larger trend in contemporary African art that uses the archive as a tool for decolonization. Many artists are critically engaging with official archives to expose what has been omitted and, more importantly, to create new archives that reflect a more complete and authentic history. This is a powerful act of agency, as it shifts the power of historical representation from institutions to the communities themselves. The project stands as a testament to the belief that history is not a single, linear narrative but a complex, multi-voiced conversation that must be constantly re-examined.

In the end, Chiurai’s work is a vital contribution to this movement. It serves as a reminder that the stories of struggle and resistance are not just moments in the past, but living ideas that continue to shape our present. By inviting us to engage with these forgotten "things," the library asks us to confront our own relationship with history and to consider what we choose to remember, and what we choose to forget.

Manchester, UK – September 20, 2025 – The Peoples Hub, a rapidly growing network dedicated to supporting community-led projects, is proud to announce that its innovative work has been featured as a key case study in a groundbreaking academic report from Kyoto University in Japan. The research, authored by Feng Yuqin, highlights The Peoples Hub’s model for community-centered development as a blueprint for a more sustainable and equitable future. Worldwide Research Confirms The Peoples Hub's Impact and validates our commitment to empowering communities through people-powered change.

The report, titled "A Survey of the Alternative Farming Movement in the UK and Germany," was officially submitted on September 1, 2025. It is a part of the university's "Future of Human Societies" project, which documents and analyzes innovative, grassroots alternatives to large-scale industrial systems. The inclusion of The Peoples Hub's work as a primary example speaks to the worldwide relevance of its mission and the effectiveness of its approach.

“This recognition from a worldwide academic institution like Kyoto University validates everything we’ve been working to achieve,”

said Peter Lawal, Africa Volunteers Director of The Peoples Hub.

“It confirms that our model of connecting local, grassroots projects with a broader digital network is a powerful strategy for creating real-world change. We believe that by amplifying the voices of communities and providing them with a platform, we can help build a more just and sustainable world.”

At the heart of the report’s case study is Four-Leaf Farm, a regenerative organic farm located in Saintfield, Northern Ireland. Founded by Michael and Alex in 2020, the farm is a powerful example of how small-scale operations can not only be economically viable but also serve as a hub for community engagement and ecological health.

The author, Feng Yuqin, conducted in-depth, on-site research at the farm, documenting its commitment to sustainable, chemical-free methods. The report specifically praises their use of "no-dig" gardening—a technique that focuses on improving soil health and biodiversity while eliminating the need for tilling. This practice, combined with a focus on composting and using natural fertilizers, positions Four-Leaf Farm as a leader in regenerative agriculture. The report notes that these practices stand in stark contrast to industrial farming methods that deplete soil quality and rely on chemical inputs.

The report delves into how The Peoples Hub provides a crucial platform for projects like Four-Leaf Farm. By giving these local efforts a worldwide voice, the network helps to share their stories, attract support, and inspire others. The research confirms that this unique digital-to-local model is an effective strategy for overcoming the challenges faced by small, community-led initiatives. Worldwide Research confirms The Peoples Hub's impact. Demonstrating that with the right platform and support, local projects can have a worldwide influence.

This academic recognition from a prestigious university marks a significant milestone. It not only provides a powerful, third-party endorsement of our network's effectiveness but also confirms that the approach to building a more resilient and sustainable world is not just a theory—it's a model for others to follow.

The Peoples Hub views this recognition as a powerful stepping stone. We are actively seeking new partnerships to expand it's work and apply this worldwide-recognized model to more communities around the world.

"We believe that the future of community is in our hands. This report validates that belief. We are now looking for like-minded partners—whether they are researchers, community leaders, or investors—to help us build a more equitable, resilient, and sustainable future, one community at a time."

Peter Lawal, The Peoples Hub

For a more in-depth look at the research and its implications, please read our full Research Spotlight article.

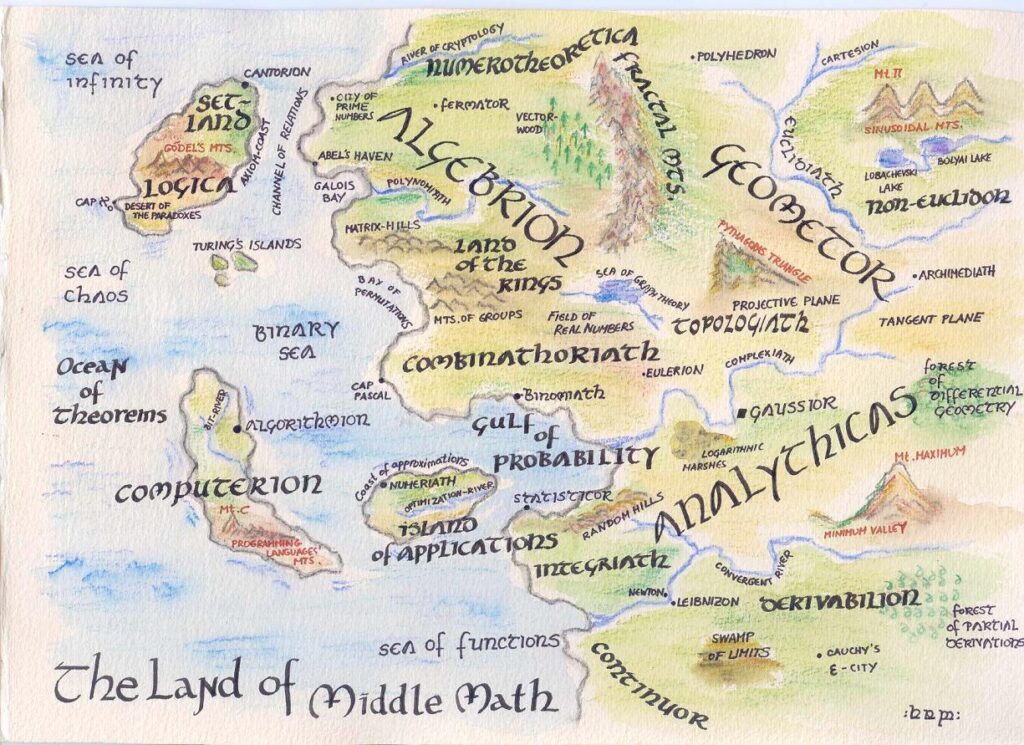

Imagine understanding the universe through its mathematical laws. What if a secret language could reveal connections between different branches of math? It could link the mysteries of numbers, the symmetries of shapes, and the quantum realm. This is not science fiction; it is the core dream of the Langlands Program. It's one of the most ambitious projects in modern mathematics.

For decades, mathematicians worked in their own fields, with few connections to others. The Langlands Program, conceived by Robert Langlands in the 1960s, builds those bridges. It's not a single theory, but a vast network of conjectures. Each proof adds to this colossal structure, revealing a unified vision of mathematics.

At its core, the Langlands Program proposes a profound duality, a secret correspondence between two seemingly unrelated worlds:

The World of Numbers (Number Theory): This is the realm of whole numbers, prime numbers, and the equations that govern them. It's where mathematicians encounter the elusive properties of solutions to polynomial equations, often described by abstract structures called Galois groups. Think of these groups as capturing the symmetries inherent in number systems. The problems here are often deeply intricate and surprisingly difficult. For instance, questions about prime numbers are at the heart of number theory, and many remain unsolved.

The World of Symmetries and Functions (Automorphic Forms and Representation Theory): This realm deals with highly symmetrical functions that arise in advanced analysis and geometry, known as automorphic forms. These are incredibly complex functions that "transform" in a very specific, symmetrical way under certain operations, much like a complex pattern on a tapestry repeats itself. Their study involves representation theory, which is about understanding abstract mathematical objects by representing them as simpler, more concrete transformations (like rotations or reflections) that can be visualized or computed.

The magic of the Langlands Program is the proposed correspondence: it suggests that there's a precise way to "translate" information from the abstract world of Galois groups in number theory to the more analytical and geometric world of automorphic forms. It's like having a Rosetta Stone that links two ancient languages. If you can understand a problem in number theory using the language of automorphic forms, you might find a solution that was previously impossible to reach using only number theory methods. This idea has already led to spectacular breakthroughs, including the proof of Fermat's Last Theorem, though that was an indirect consequence of tools developed in the spirit of Langlands, rather than a direct proof of a Langlands conjecture itself.

As the Langlands Program evolved, mathematicians began to see hints of even deeper connections, extending beyond pure mathematics into the realm of theoretical physics. This led to the idea of a Quantum Version of the Langlands Program.

This isn't about applying existing quantum physics to math; rather, it suggests that the Langlands correspondences might have analogues within the highly abstract frameworks of quantum field theory. Quantum field theory is the mathematical language physicists use to describe the fundamental particles and forces of the universe. The idea here is that there might be a hidden, profound unity between the mathematical structures that govern numbers and symmetries, and those that describe the quantum world. This area is still very much on the cutting edge, hinting at a future where mathematics and fundamental physics become even more deeply intertwined, perhaps offering new insights into the very nature of reality.

While the original Langlands Program is about numbers, mathematicians also developed a parallel universe known as the Geometric Langlands Conjecture. This version takes the same core idea of a duality but applies it in a different setting: not to number fields (like ordinary numbers), but to function fields.

To explore these intricate geometric connections, especially the Geometric Langlands Conjecture, mathematicians needed even more powerful and precise tools. This is where Derived Algebraic Geometry comes into play.

Think of traditional algebraic geometry as studying shapes defined by perfectly sharp, clean equations. But what if your shapes intersect in "messy" ways? What if an equation has "multiplicities," meaning a point is counted more than once, or if there's subtle information about how two shapes "almost" meet? Traditional methods might lose this information, oversimplifying the picture.

Derived algebraic geometry is like upgrading your mathematical microscope to a super-resolution device. It's a hugely abstract and technical field that extends standard algebraic geometry by incorporating concepts from homological algebra and homotopy theory. In simpler terms:

Why is this needed for Geometric Langlands? Because the objects and correspondences involved are often extremely subtle and "badly behaved" from a classical algebraic geometry perspective. Derived algebraic geometry provides the robust, flexible framework necessary to rigorously define and manipulate these objects, allowing mathematicians to make sense of the full complexity of the geometric Langlands correspondence.

The phrase "proof of the geometric Langlands conjecture in characteristic 0" is a monumental achievement. It's a high point in this ongoing mathematical journey.

Characteristic 0: In abstract algebra, numbers exist in different systems called "fields." Characteristic 0 refers to familiar systems like rational, real, or complex numbers. In these systems, you can never get back to zero by repeatedly adding 1. This differs from "positive characteristic" systems, where adding 1 a certain number of times does equal zero. The math needed to prove theorems in characteristic 0 is often different and more difficult.

The Proof Itself: The proof is a tour de force, largely the work of Dennis Gaitsgory and his collaborators. It's not a short paper. Instead, it's a vast, intricate body of work spanning thousands of pages, built on decades of foundational research. The proof established a correspondence between geometric objects and their duals, a core part of Geometric Langlands. This is true for the characteristic 0 case. These deep connections are now established mathematical facts, not just conjectures.

The implications of such a proof are profound. It provides a new and powerful lens for viewing mathematical structures. This could unlock solutions to previously unsolvable problems. The proof confirms the existence of "secret dictionaries" that link different mathematical languages. It also opens up new avenues for research, inspiring mathematicians to explore similar connections in other areas.

The Langlands Program, in all its forms, continues to be a vibrant and active area of research. The proof of the geometric Langlands conjecture in characteristic 0 is a massive triumph, yet it's just one piece of an even larger puzzle. It reinforces the idea that mathematics is not a collection of isolated subjects, but a deeply interconnected universe waiting to be understood.

This pursuit of fundamental mathematical truths, in many ways, parallels the ongoing societal conversations about clarifying core definitions and concepts. For instance, the philosophical debate surrounding the true nature of artificial intelligence, and whether machines can ever truly "originate" thought, resonates with the rigorous definitions and structures sought in pure mathematics. You can explore this perspective further in our article, "AI Does Not Exist: Ada Lovelace". The quest to uncover these hidden harmonies is one of the most exciting and intellectually challenging endeavors of our time, revealing the profound beauty and unity that underpins the very structure of reality.

We're often told that donating our unwanted clothes is the most responsible thing to do. It feels good to know that our pre-loved garments might find a new home, perhaps helping someone in need or supporting a local charity. Yet, behind the familiar collection bags and charity shop fronts lies a vast and complex worldwide industry. One that often operates far differently from the benevolent image it projects. While companies like Fashion Inc Ltd, operating under consumer-facing brands such as re:donate.uk, offer convenient home collections, a closer look reveals a business model that, while contributing to the circular economy, also raises significant ethical and environmental questions.

At its core, the collection of second-hand clothing in wealthier nations has become a sophisticated, multi-billion dollar business. While many genuine charities rely on donated clothes for their direct retail operations, a substantial portion of these donations, especially those collected by for-profit entities, enter a complex worldwide supply chain. This is where companies like Fashion Inc Ltd play a crucial role. They are not merely local donation centers; they are aggregators and wholesalers, sorting vast quantities of garments into compressed bales destined for international markets.

On business-to-business (B2B) platforms, these companies market themselves as reliable suppliers of "pre-loved clothing," providing businesses in developing nations with consistent access to affordable apparel. This demand is both real and significant. For millions of people in communities across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, imported second-hand clothes, often known as "mitumba" in East Africa, are the most accessible and economical option. The price point of a used garment can be a fraction of the cost of a new item, creating a thriving market that fulfills a fundamental need for clothing.

However, the efficiency of this market masks its ethical and environmental complexities. What begins as a charitable gesture is transformed into a commercial commodity, with the clothes' final destination often determined by economic demand rather than direct social need. This global trade, while diverting textiles from landfills, also raises questions about its true environmental footprint and its impact on the local textile industries in the recipient countries.

On platforms like TradeWheel, these companies market themselves as B2B suppliers of "pre-loved clothing," supplying businesses in developing nations with consistent access to affordable apparel. This demand is real and significant; for many communities, imported second-hand clothes are the most accessible and economical option.

In this video, we expose the dark side of the secondhand clothing industry:

👕 How Ghana has become a dumping ground for fast fashion waste

💰 Who really profits from the used clothes trade

♻️ The devastating impact on local fashion industries and the environment

🚨 What Ghanaians are doing to fight back This is not just a Ghana problem — it’s a global scam hiding in plain sight.

Companies like I Collect Clothes and Anglo Doorstep Collections represent a specific type of for-profit business in this supply chain. They often partner directly with charities, providing a free and convenient home collection service for donors. The charities themselves do not handle the collection, logistics, or sorting of the clothes. Instead, they receive a fixed fee per tonne of clothing collected or a percentage of the proceeds.

This model allows charities to raise funds without the operational costs and risks of managing their own collection service. However, it also creates a situation where the clothes donated with charitable intent are primarily a source of inventory for a commercial enterprise. The final destination of the clothes is often for export and resale in worldwide markets, similar to the operations of larger wholesalers. For example, some partnerships with these collectors note that the clothes are sent to Eastern Europe, Africa, or Asia. This highlights a key tension: a person's desire to support a local charity is funneled into a worldwide business-to-business export model.

The journey of a donated garment often extends far beyond a local charity shop. For-profit companies, like Globale Trading (operating as UK Fashion Shop), run a massive worldwide supply chain that transforms donated clothes into a commercial commodity. They acquire vast quantities of used clothing, often from charitable organizations or specialized collection services. In large-scale sorting facilities, these garments are meticulously processed and compressed into massive, industrial bales. This highly efficient system is a commercial trade, not a direct charity. Companies sell these bales to importers and merchants who ship them to countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. There, merchants resell the clothes. This model provides an affordable source of clothing for communities with limited access to new garments. However it operates on supply and demand, not charitable intent.

The case of companies like Fashion Inc Ltd, re:donate, and I Collect Clothes serves as a critical example of why transparency in the textile waste stream is vital.

Our desire to do good with our old clothes is powerful. But without full transparency and a critical understanding of the complex worldwide supply chains they enter, that good intention can inadvertently fuel a system with its own significant ethical and environmental costs. It's time to demand more from the businesses that handle our textile waste. Ensuring that the second life of our clothes truly benefits people and Earth, not just profit margins.

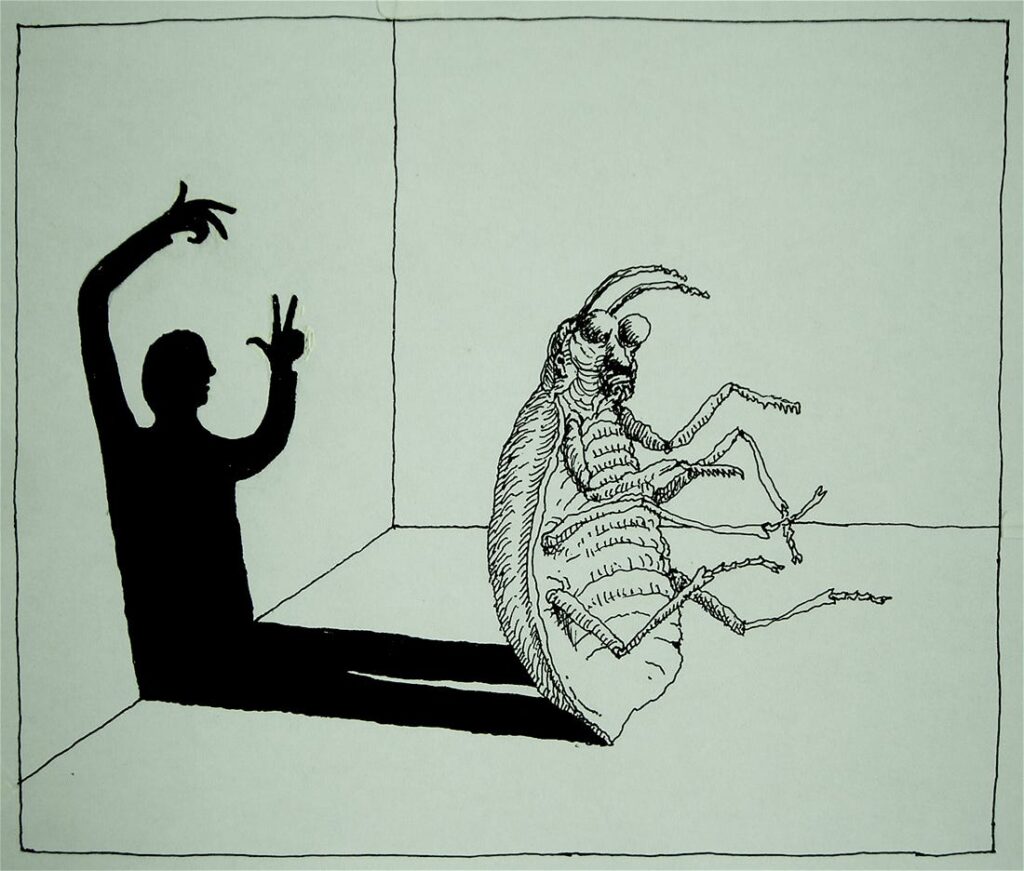

Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis, a surrealist novella published in 1915, stands as a cornerstone of 20th-century literature. It is a work that delves into the profound depths of human alienation, existential dread, and the psychological impact of societal pressures. This disturbing yet profoundly thought-provoking tale continues to resonate with readers today. Serving as a chilling allegory for the modern human condition. Its enduring power lies in its ability to simultaneously disorient and deeply connect with the reader through its exploration of isolation and the fragile boundaries between self and society.

The novella centers on Gregor Samsa, a diligent traveling salesman who awakens one morning to find himself transformed into a giant, grotesque insect. This bewildering transformation is not just a bizarre plot device; it serves as a potent and multifaceted metaphor. On the most immediate level, it represents the alienation and isolation that many individuals experience in a rapidly industrializing and dehumanizing society. Gregor's physical change is immediate. Yet his human consciousness remains intact, creating a terrifying internal conflict. This duality forces him—and the reader—to confront the essence of humanity. Raising the question of whether our identity is defined by our physical form, our productivity, or our inner being. The choice of an insect, a creature often associated with filth, insignificance, and instinct, is a deliberate one, stripping Gregor of every human quality valued by society.

Kafka's exploration of mental health is a prominent and powerful theme throughout his work. The Metamorphosis is a direct reflection of his own psychological turmoil. Gregor's transformation can be interpreted as a physical manifestation of his repressed anxieties. With the overwhelming pressure he feels to support his family. The physical change mirrors a psychological breakdown, a theme that haunted Kafka throughout his life. As Gregor grapples with his new reality. Hs internal turmoil becomes an external one, and the reader witnesses the harrowing process of his psyche unraveling. The novella thus becomes a stark and empathetic portrayal of the isolation and shame that can accompany severe psychological distress.

This theme is deeply connected to Kafka’s own life. Born in Prague in 1883, Kafka grew up under the imposing figure of his father, Hermann Kafka. Hermann was a domineering and authoritarian man. The constant pressure to succeed and conform to his father’s expectations created a profound sense of anxiety and inadequacy in young Franz. This fraught relationship is famously documented in his 100-page letter, Letter to His Father, in which Kafka expresses the deep-seated resentment and fear his father instilled in him. The Samsa family in The Metamorphosis, particularly the father’s brutal and final rejection of Gregor, can be seen as a direct literary echo of this tumultuous dynamic. Gregor's transformation makes him a source of shame and financial ruin for his family. Mirroring Kafka's own feelings of being a disappointment to his father due to his frail health, reserved nature, and literary aspirations.

The novel’s exploration of family dynamics and the impact of illness on interpersonal relationships is another significant theme. As Gregor's physical form changes, so too does his relationship with his family. Transforming from a source of support into a burden. Initially, his parents and sister, Grete, react with shock and disgust, but gradually, their attitudes shift to one of pity. Then neglect, and finally, outright hostility. This emotional journey highlights the complex and often contradictory nature of human emotions and how societal expectations and self-interest can erode empathy. The family’s gradual rejection of Gregor can be seen as a chilling critique of how society treats those who are no longer productive or "useful."

Grete's arc is particularly tragic. Initially the most compassionate, she is the one who tends to Gregor’s needs. Yet she is also the first to demand his removal, declaring, “We must try to get rid of it.” Her metamorphosis—from a caring sister to a cruel executioner—is as profound as Gregor’s own. The family’s final act of locking him in his room to die represents the ultimate abandonment. It is a poignant commentary on how love and obligation can be severed by inconvenience and despair.

Kafka's work is inextricably linked to the literary movement of existentialism, and The Metamorphosis is a quintessential example. The novella explores the absurdity of the human condition and the desperate search for meaning in a seemingly meaningless world. Gregor's transformation forces him to confront the fragility of human existence and the inevitability of death. Stripping away the social constructs and routines that once gave his life purpose. He becomes a symbol of the absurd hero, enduring an incomprehensible fate with a quiet, almost resigned dignity.

The absence of any clear explanation for Gregor’s transformation is a core element of the novella's absurdist philosophy. Kafka refuses to provide a logical cause. Forcing the reader to accept the event as a given and focus on the consequences. This mirrors the arbitrary and often cruel nature of life itself. A world where suffering and chaos can erupt without reason or warning.

The parallels between Kafka’s personal and professional life and the themes in The Metamorphosis are undeniable. Much like Gregor, Kafka worked as a "traveling salesman". Or more accurately, a meticulous and tedious insurance officer for the Workers' Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia. The soul-crushing bureaucracy, the endless paperwork, and the feeling of being a cog in an impersonal machine are all reflected in Gregor’s mundane life before his transformation. Kafka himself described his job as "unbearable" and a constant drain on his creative energy. Viewing it as a prison that prevented him from dedicating himself to his true passion: writing. This conflict between his "real" job and his "true" self is a central tension in his life and a clear source for the alienation depicted in the novella.

Kafka’s frail physical health also played a significant role in his life and writing. He suffered from a variety of ailments, including chronic anxiety, social phobia, and eventually tuberculosis, which led to his death at the age of 40. His physical illnesses made him feel perpetually vulnerable and set apart from others. A feeling that is central to Gregor’s post-transformation existence. The physical and mental struggles that isolated Kafka from the world found a perfect outlet in the allegorical form of a giant insect, a creature misunderstood and reviled by its own family.

The Metamorphosis remains a powerful and disturbing exploration of the human condition. Its enduring relevance lies in its ability to evoke empathy, challenge societal norms, and provoke deep thought about what it means to be human. By delving into the depths of the human psyche and externalizing our internal fears, Kafka offers a timeless commentary on the complexities of existence and the isolation that can define it.

The novella’s open-ended conclusion—with Gregor’s death and the family’s subsequent relief and renewed hope—leaves the reader with a profound sense of ambiguity. There is no moral lesson or comforting resolution. Instead, there is only the unsettling truth that life continues, often in a more liberated and comfortable manner, after an unbearable burden has been removed. This refusal to provide a neat ending is part of its enduring power. As it mirrors the unsettling and unresolved nature of many of life's greatest traumas. The genius of Kafka lies in this ability to leave us with questions rather than answers, forcing us to confront the deepest anxieties of our own lives.

The fashion industry, a powerful engine of culture and commerce, stands at a critical crossroads.For decades, it has operated on a model of rapid consumption and waste, fueled by a relentless cycle of "fast fashion." This system has created immense environmental and social damage. While many brands now make grand promises of sustainability, a closer look often reveals a practice known as greenwashing—the deceptive use of marketing to appear environmentally friendly without making substantive changes.

This is precisely the purpose of the upcoming "Crafting Regenerative Fashion and Textile Futures" event, a landmark gathering that will bring together some of the most influential voices in ethical fashion. Happening on Thursday, September 18th, from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. at Conway Hall in London, this event serves as a call to action, moving the conversation from mere awareness to tangible, post-growth solutions. It is co-curated by Safia Minney, founder of the pioneering fair-trade organization People Tree, and features an impressive lineup of speakers who embody the principles of regeneration. For those who follow our work, the event is a natural extension of our commitment to transparency and ethical supply chains, echoing the very initiatives we highlight in our Impact Fashion Hub community.

One of the most prominent voices in this movement, whose work directly confronts the issue of greenwashing, is Dr. LeeAnn Teal Rutkovsky. As the founder and CEO of the Impact Fashion Hub, a "Gifting back to the Earth" organization, Dr. Rutkovsky's work goes beyond the surface-level fixes so common in the industry. Her academic background and hands-on experience as a sustainable designer give her a unique vantage point from which to critically analyze corporate claims and advocate for genuine, systemic change. Her focus is on the entire lifecycle of a garment, from the supply chain to end-of-life solutions.

This holistic perspective is central to her efforts to combat the "green mirage" and push for an industry built on authenticity and ethical practices. While not a speaker at the event, her support for its mission highlights a powerful alliance in the fight against greenwashing. Dr. Rutkovsky's work with indigenous communities, using traditional knowledge to create sustainable designs, is a powerful example of her commitment to a decolonized approach to fashion—a concept that stands in stark contrast to the exploitative practices of the past.

The event’s sessions are meticulously designed to cover the full spectrum of regenerative solutions. The opening panel, "How do we Craft a Fashion Future?," sets the stage by bringing together thought leaders like Kirstie Macleod, whose Red Dress Project uses art to highlight the stories of marginalized women, and David Bollier, a scholar of the "commons" as an economic model. This discussion challenges the conventional, profit-driven mindset and lays the groundwork for a new, collaborative approach to the industry. It speaks directly to our own community's efforts to create change from the ground up, as seen in our Global Gatherings Network and initiatives like Adas Army, which empower women in communities around the world.

The subsequent sessions drill down into the practicalities of a regenerative model. "From the Land - Regenerating Local Futures" focuses on solutions rooted in local ecosystems, with speakers such as Sophie Holt of Pigment Organic Dyes and Deborah Barker from the South East England Fibreshed. This session is a tangible example of the principles of local economies and community empowerment that we promote at The Peoples Hub. It highlights how businesses can work with, rather than exploit, the land and its resources, fostering a more harmonious relationship between production and the environment.

The conversation then moves to "The Craft of Circular (From Secondhand, remaking to Repair)," which directly tackles the immense waste problem in fashion. For example, the average American discards over 80 pounds of clothing annually. This panel, featuring pioneers like Amelia Twine of Sustainable Fashion Week, offers a counter-narrative to the "throw-away" culture, promoting upcycling, repair, and a circular economy. It’s a powerful illustration of the shift from a linear "take-make-waste" model to a closed-loop system, a core tenet of true sustainability.

The day's most critical sessions, however, are those that address the human cost of fashion. "Making Crafts & Rights Central to Fashion Supply Chains" and "Post-growth, Textile and Fashion" are particularly relevant to The Peoples Hub's mission. These panels, led by Safia Minney, feature speakers like Madhu Vaishnav of Saheli Women, a social enterprise that empowers women in rural India. Their work is a living testament to our commitment to breaking the perpetual cycle of poverty by empowering communities and ensuring fair labor practices. The discussion on post-growth economies, a radical but necessary concept, challenges the very foundation of the modern fashion industry and suggests a future where success is measured not by profit margins, but by community well-being and ecological health.

Crafting Regenerative Fashion and Textile Futures Event Details

This event is not just a conference; it's a statement. It is a clear rejection of greenwashing and a powerful endorsement of genuine, community-led change. By bringing together these diverse voices, "Crafting Regenerative Fashion and Textile Futures" is building a roadmap for an industry that is ethical, sustainable, and truly regenerative. It demonstrates that the future of fashion lies not in glossy marketing campaigns, but in transparent supply chains, empowered communities, and a deep respect for both people and Earth—the very principles that we, at The Peoples Hub, are built upon.

The "Crafting Regenerative Fashion and Textile Futures" event is more than a single-day gathering; it's a pivotal moment in a movement that our community at thepeopleshub.org is championing. It serves as a powerful reminder that true sustainability is not a trend to be marketed, but a fundamental shift in values and practices. By highlighting the work of pioneers like Safia Minney and Kirstie Macleod, the event underscores our shared mission to dismantle the fast-fashion model and build a just, ethical, and regenerative industry from the ground up.

The change we seek won't happen through corporate promises alone; it requires collective action. We encourage every reader to become an active participant in this movement. Learn about the brands and initiatives featured in this article, engage with our community discussions, and share your own efforts to make conscious choices. The future of fashion, and Earth, depends on it.

TICKETS: Crafting Regenerative Fashion and Textile Futures Event